By Peter Coles

Canonbury, that sedate corner of urban tranquillity just two miles due north of St Paul’s cathedral, is home to more curiosities than many parts of London. Some are well known, like the delightful, exposed stretch of the New River, a project started in 1602 and completed in 1613, to bring drinking water to central London from the River Lea near Ware in Hertfordshire (see also our article linked to Sir Hugh Myddelton, who oversaw the project).

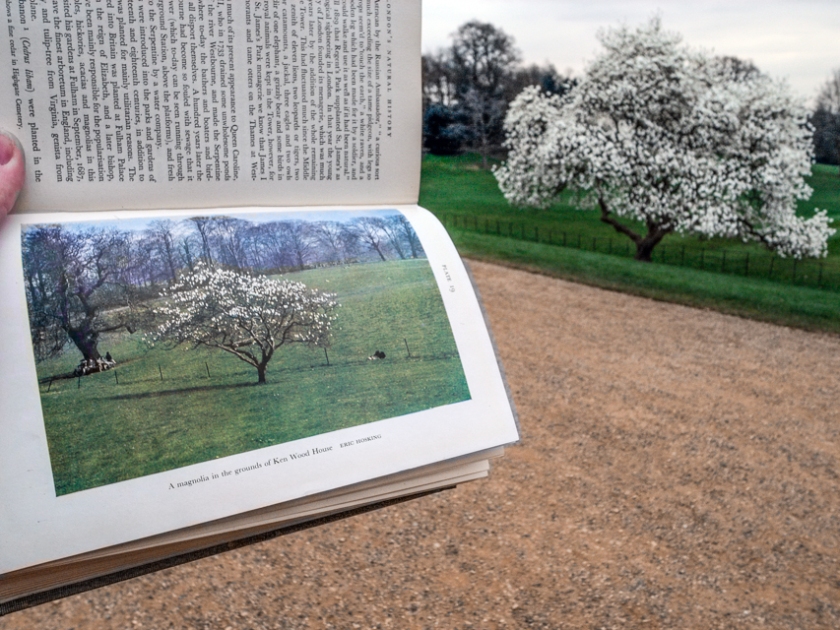

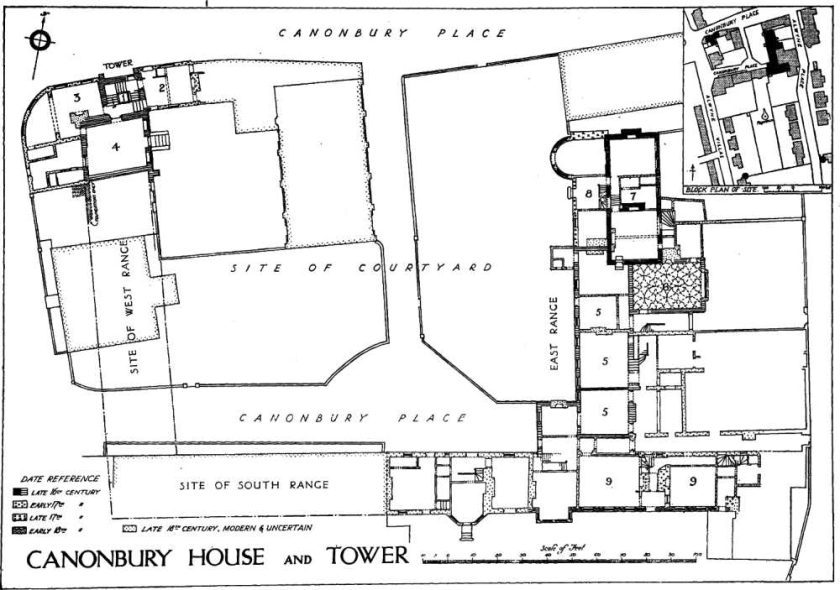

And then there is Canonbury Tower – a very unusual Tudor brick tower built between 1509 and 1532 by Prior William Bolton of St Bartholomew’s Priory in Smithfield (on the site of St Bartholomew-the-Great). The Tower was part of his redesign of the extensive 13th century Canonbury Manor, which belonged to the canons of St Batholomew’s. This once covered all of today’s Canonbury Place, including a large park and gardens, complete with an octagonal house – another Canonbury curiosity, which can still be see today in Alwyne Villas.

But few are aware that, hidden in a private garden behind the tower and the adjacent Canonbury House, is a sprawling, gnarled, black mulberry tree that might turn out to be one of the oldest in London.

A 16th century skyscraper

Canonbury Tower is fascinating in its own right. When Henry VIII seized Canonbury Manor during his Dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, it eventually passed down to his First Minister, Thomas Cromwell, who oversaw the Dissolution. Cromwell lived here for a year before his fall from grace and execution in 1540. In 1570 the Mansion passed to Sir John Spencer, a favourite of Elizabeth I, who became Lord Mayor in 1590. In the early 1600s, Sir Francis Bacon lived here and, later, Oliver Goldsmith.

The Tower has some extraordinary carved fireplaces, Tudor cubbyholes and a dark, oak-panelled room with a few remnants of the paraphernalia of freemasonry. Much of the Masonic symbolism added to the wood carvings and decorations was commissioned by Spencer, who was a prominent Rosicrucian. On Spencer’s death in 1610, the mansion passed down to his son-in-law, William Compton, Earl of Northampton, who had eloped with Spencer’s daughter, Eliza, who was hiding in a bread basket lowered from an upstairs window. The Manor has passed down in the Spencer-Compton family ever since and is still owned by the Marquess of Northampton.

Spencer was a friend of Francis Bacon, the philosopher and parliamentarian under both Elizabeth I and James I, who came to live at Canonbury Manor from 1616-25. Like Spencer, Bacon was a Rosicrucian, and the first Grand Master of modern English Freemasonry. The Tower became the home of the Masonic Research Centre from 1998-2012.

The oldest mulberry in London?

Did any of these illustrious early residents plant the mulberry tree? If so, it could be anywhere between 400 and 500 years old, placing it in the ranks of the oldest surviving mulberries anywhere in England – and certainly the oldest within walking distance of the City. There are very old mulberries in the ancient orchard at Syon House, which are also thought to be 16th or at least 17th century. Old mulberries were noted there in 1548 by William Turner, the botanist and apothecary to Lord Somerset who inherited the Bridgettine monastery after the Dissolution and built a house there. But, although well inside the M25, Syon House is in Brentford, 13 miles away from the City. Meanwhile, another very old mulberry at Charlton House, which is thought to date from 1611, is 7 miles from the City.

Could the Canonbury mulberry really be Tudor and as old, or older, than the Syon House trees? It is impossible to tell for sure, without invasive analysis. But it does share many of the hallmarks of a very old tree: It has collapsed and much of the trunk is lying horizontally. Branches trailing along the ground have started to grow upwards like new trunks, some distance from the original bole. The core of this bole is hollow and split, with the familiar burrs of a black mulberry, making it very difficult to measure its girth to assess its age.

There is a black mulberry at Hatfield House that was possibly planted by John Tradescant when he was Head Gardener from 1610-15, but may well pre-date him by fifty years, as it has also been attributed to Princess Elizabeth, when she lived there before becoming queen . The Hatfield mulberry, though has been pollarded and, while hollow, is squat and not leaning or lying down. Meanwhile, Christ’s College, Cambridge has records of purchasing and planting black mulberry trees in 1608. One of these – the celebrated ‘Milton mulberry’ – survives on a mound in the Fellow’s Garden and shares several features with the Canonbury tree.

There is, then, every possibility that the Canonbury mulberry is very old – the walled garden where the tree stands features in old plans of the Manor. Prior Bolton seems to have been familiar with mulberries and may have planted one or more at St Bartholomew’s Priory, which he rebuilt. There are records of a very old mulberry tree still surviving in the 19th century, adjacent to St Bartholomew-the-Great (with remains of the Priory) and some evidence for a mulberry garden next to the Infirmary. There is a fine mulberry tree there today, although not more than 100 years old, but it does symbolise the ancient connection.

Another possibility is that Francis Bacon planted the Canonbury mulberry. Bacon was a cousin of Robert Cecil, son of William Cecil, the powerful Lord Burghley in the reign of Elizabeth I. Robert was responsible for rebuilding the Tudor Hatfield House and gardens in the Jacobean style. James I had persuaded Robert to accept the Old Palace and manor at Hatfield in exchange for the splendid Theobalds, which Robert had inherited from his father. We know that around 1611 Robert sent his gardener, John Tradescant, abroad to bring back mulberry saplings. He apparently planted around 500 at Hatfield, as part of James’s sericulture project, though only one survives today – and that is a corner feature of the Tudor knot garden, not apparently a vestige of a plantation. Robert Cecil and Bacon were not exactly on friendly terms, but Tradescant may have had a mulberry going spare for Bacon to plant at Canonbury – if there wasn’t one there already….

__________________

Thanks to Nicola and Gavin Ralston for inviting me to look at the tree. Nicola is writing her own account of the tree for the Canonbury Society, due out in March-April 2018.